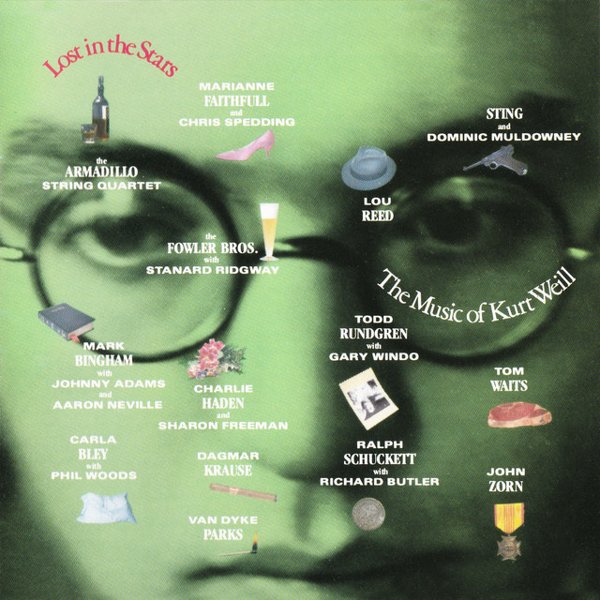

Lost in the Stars: The Music of Kurt Weill

“Mack the Knife” became a standard and The Doors covered “Alabama Song” on their first LP, but it still must’ve seemed like a bit of a curiously anachronistic idea for MTV-era rock stars to interpret the work of Kurt Weill. Maybe it’s because Weill’s compositional mixture of cabaret theatrics, German-Jewish melodic traditions, and acerbic social commentary feels deeply tied into interwar 20th Century culture in the looming shadow of fascism — an atmosphere that America was more than happy to push to the fringes in the heart of the ‘80s. But as Hal Willner’s Lost in the Stars easily proves, Weill’s work is readily adaptable to the avant-conversant sides of art rock, no wave, and post-punk. The marquee names are well up to the task, whether it’s Sting skulking with arch malevolence through a Dominic Muldowney-abetted “Ballad of Mac the Knife,” Lou Reed casually facing the onset of middle age with a nonchalant shrug on a pop-soul-tinged “September Song,” and Tom Waits’ nightmare carnival tromping through Threepenny Opera anthem “What Keeps Mankind Alive” like the final reckoning of a warning left unheeded for more than half a century. Maybe the two most audacious adaptations are also the starkest contrasts: Marianne Faithfull’s performance of the Bertolt Brecht adaptation “Ballad of the Soldier’s Wife” is steeped in a Dixieland-redolent arrangement that underscores the bitter rasp of her voice and builds to her astoundingly devastated-sounding delivery of the final verse’s morbid punchline. Meanwhile, Todd Rundgren’s “Call From The Grave / Ballad In Which MacHeath Begs All Men For Forgiveness” sets up a glossy, danceable synthpop arrangement that sounds so deeply entrenched in the era’s contemporary idea of cutting-edge tech that it seems attuned to the idea that the social ills that inspired Threepenny Opera in the first place have only gotten more frantic and pressurized with time — an idea that comes through even more clearly in Rundgren’s horror-struck screaming. Meanwhile, the jazz and avant ensembles — Charlie Haden and Sharon Freeman in reflective repose on the bass-and-strings “Speak Low,” the tense scattergun chaos of John Zorn’s mini-operatic “Der kleine Leutnant des lieben Gottes,” Henry Threadgill’s symphonic brass tempest “The Great Hall” — take Weill’s melodies to the outskirts.