If one only tuned into the biggest pop moments of the 1980s (or at least watched a few VH1 specials about the decade), the earnestness of such star-studded projects like Bob Geldof and Midge Ure’s “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” and the Michael Jackson and Lionel Ritchie-penned “We Are the World” suggested that while pop music might be a force for good, its good works depended on the idea that Africa was a charity case. To be clear, the Ethiopian civil war led to a famine that produced a true humanitarian crisis and despite the patronizing aspect of these projects, both were genuinely well-intended. At the dawn of the video era, a broadcast of multi-millionaire pop stars gathered in the studio interspersed with footage of children malnourished in Ethiopia might be the lone glimpse that many Americans would ever get of a continent of over 50 different countries and hundreds of different cultures and languages. It was a warped mirror suggesting that the relationship between Africa and the West was strictly flowing in one direction, from the gilded First World back to the impoverished Third World.

But beyond the benevolent grandstanding, the decade also revealed a true transatlantic exchange between the two. Paul Simon has become the poster boy for this sort of exchange, first as a member of the USA for Africa supergroup and then a few years later enjoying massive success thanks to his multi-platinum 1986 album Graceland, which wove together American pop and South African musical styles. Simon brought African music to the world stage despite accusations of cultural appropriation, breaking the anti-apartheid cultural boycott of South Africa at the time, which was exerting massive political and financial pressure on the country. Graceland grew out of Simon’s true thrill at the sounds emerging from the impoverished townships of Soweto at the time, specifically the spry rhythms and ineffable harmonies of isicathamiya and mbaqanga.

Isicathamiya, an acapella singing style that emerged among the Zulu people of South Africa, is an example of just how music flows between cultures, mutating in the process. Some musical scholars trace the form back to the 19th century, when American minstrels and vaudeville troupes toured the country in the pre-Civil War era, where these songs soon intermingled with Zulu traditional music. Mbaqanga also featured similarly tangled musical roots. It arose in the urban centers surrounding Johannesburg, a mixture of South African vocal stylings, the rhythms of native marabi and kwela music, with a dollop of American big band jazz added on top.

Could Simon hear the bits of American musical DNA in these exotic African sounds? Simon came by this music on a bootleg cassette given to him by Norwegian musician Heidi Berg and became enamored of it, telling Rolling Stone at the time that it reminded him of the rhythm and blues of his childhood and was “very good summer music, happy music.” (According to Berg, it was originally her idea to meld these South African influences to her own music, only to have Simon claim them himself.)

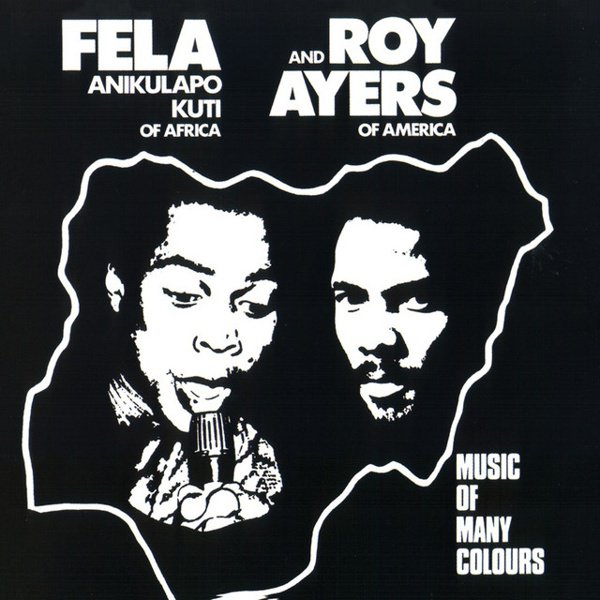

He wasn’t the only one enthusiastic about Africa’s output. Ginger Baker was an early booster of Fela Kuti, while Brian Eno flew to Accra to produce The Pace Setters, the lone album by Ghanaian group Edikanfo, in 1981. Peter Gabriel was also an African music enthusiast, which in the 1980s would manifest in his stunning duet with Senegalese singer Youssou N’Dour on “In Your Eyes.” The African music that both Gabriel and Simon amalgamated with their own songs contributed massively to the global success of both stars in that decade.

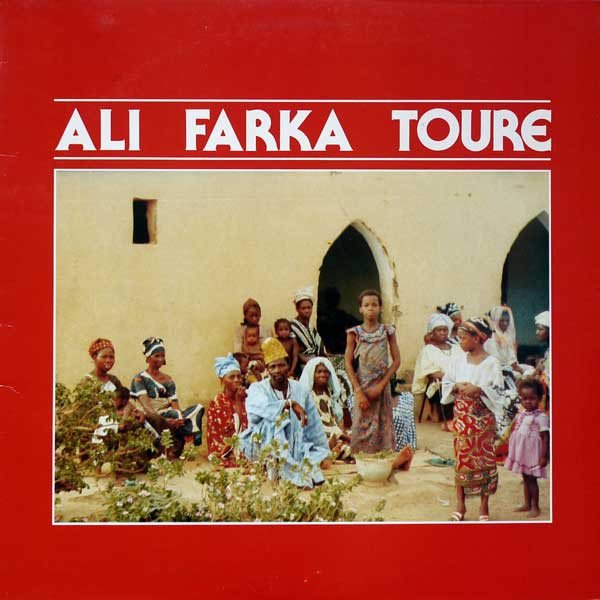

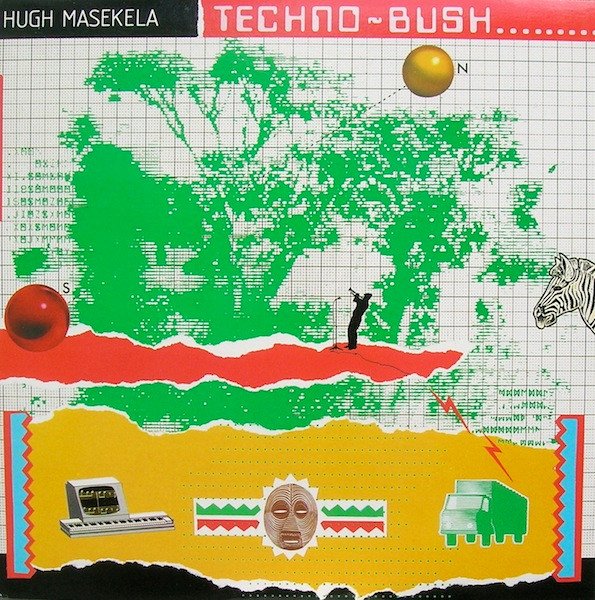

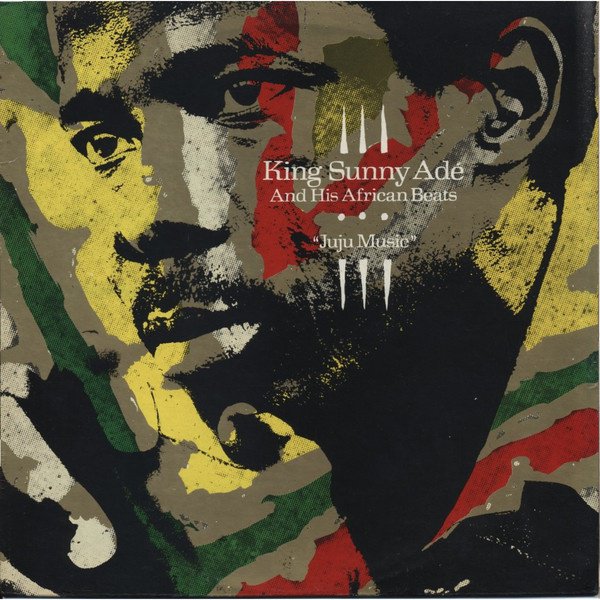

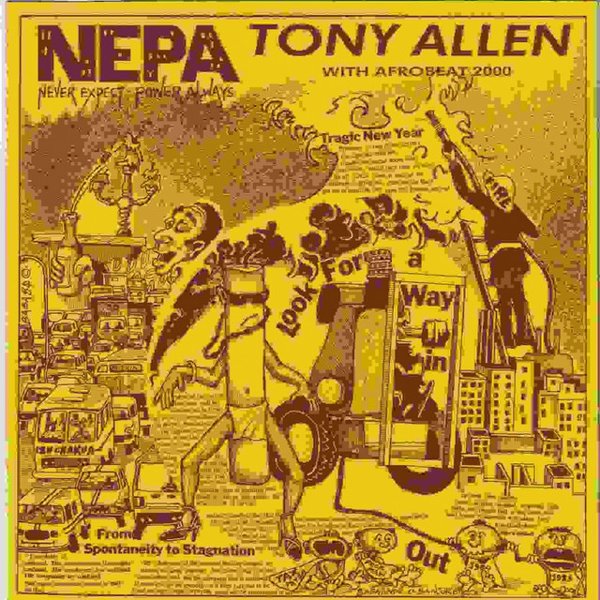

On the flip side, African artists themselves also emerged on the world stage like never before and found new audiences in the West. Much like Simon could hear a sound that evoked memories of his favorite songs, ‘80s music fans could hear something new coming out of Africa. One can hear the funk of James Brown coursing through Fela’s Afrobeat. King Sunny Ade is a guitar god regardless of genre. The blues coursed through Ali Farka Touré’s Malian music, and even if you don’t understand Wolof, Youssou N’Dour had a commanding voice.

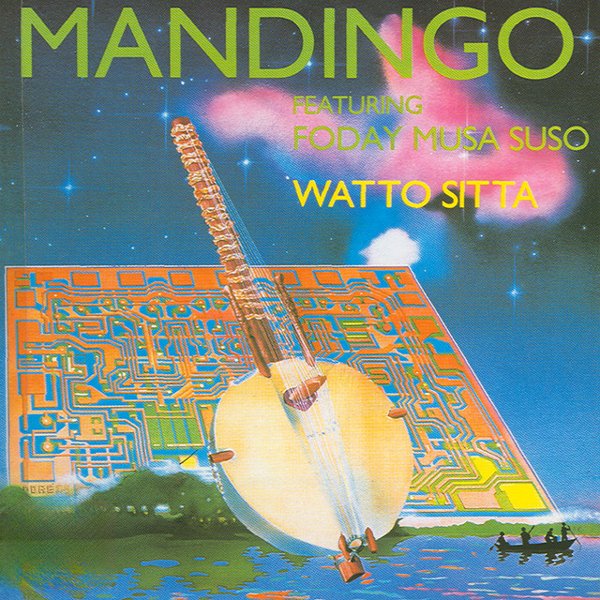

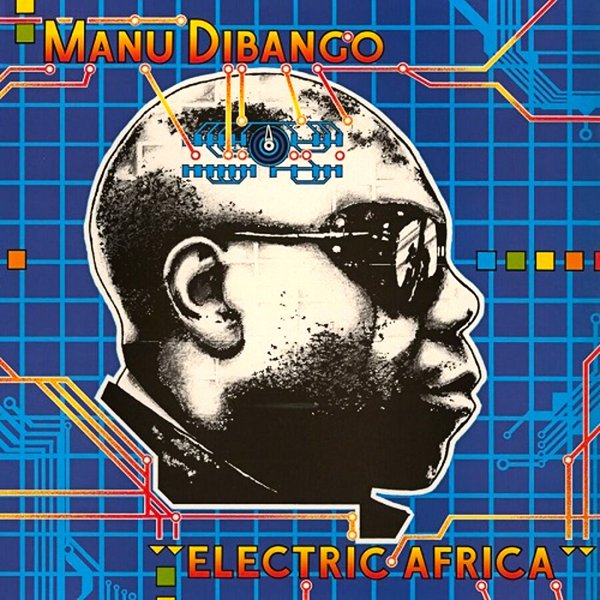

These African artists (to name just a scant few) garnered large crowds outside of their native Africa, mingling with pop stars and booking studio time in upscale studios, while also enjoying access to greater record distribution and utilizing new-fangled musical gear to create a fascinating hybrid. Years before the concept of “world music” would take root amid CD racks, something new was emerging thousands of miles away.

Take this blurb from the back of a random comp – slotting Jermaine Jackson and Billy Ocean alongside African pop acts like Richard Jon Smith and Hugh Masekela – about this new music “which takes the world’s myriad musical traditions…and injects them with the intensity and urgency of Western pop, using the full palette of contemporary instruments and state-of-the-art recording techniques.”

Many of the African musicians that gained exposure in the West were already stars at home, and while a few only released now-coveted records in their native countries, some made significant inroads into U.S. pop radio. Some longtime African music fans and critics argued that a sanitized, rustic, or uniform “African sound” of “world music” was as foolish as the aforementioned fundraising hits of old, and as popular as these glitzy singles may have been, they also served to obscure an emergent sound – both variegated and electrifying – that might have otherwise made it into MTV’s rotation.

In embracing the new technologies back in their home countries, these African artists laid the foundation for the decades of innovative hybrids that have followed, be it “burger highlife,” “Afrobeats,” “bubblegum kwaito,” “hiplife,” “amapiano,” or all of the other amalgams that have since emerged. As African music increasingly vies for prominence on the world stage in the border-eradicating era of streaming, increasingly Africa can reverse the 80’s anthem and proclaim: “We are the World.”