In the beginning, it was a joke — a way for disgruntled hardcore fans in Washington, DC to poke fun at themselves and their friends by stepping away from the rigid masculinity and de rigueur anger that they felt had started to strangle the genre. Decades later, it was everywhere, seeping into pop culture at almost every conceivable level. Emo music and culture found its way into rock, pop, dance and hip-hop music. It was in fashion, internet culture, and even movies. Its influence was ubiquitous to a degree that would likely shock its early adopters, and in many ways its hardcore origins have become so distant as to be irrelevant. Emo began as hardcore with shades of grey, but has become more of an aesthetic than a musical genre, like punk or goth – a general attitude of self-absorption flexible enough to adapt to evolving musical trends.

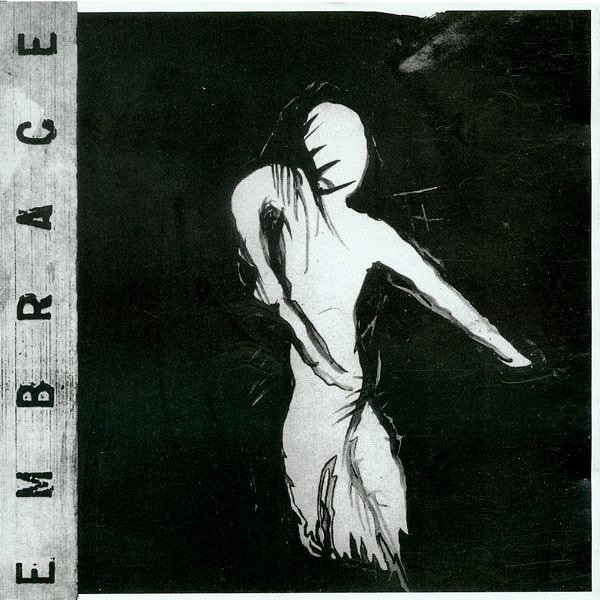

But emo was simply a variation of hardcore at its formal birth, around 1985. There were precursors – the romantic pop-punk of Buzzcocks and the emotionally complex, experimental Hüsker Dü – but Washington DC-based Rites of Spring’s seismic impact was the big bang moment. Rites of Spring added musical texture, longing and self-doubt to hardcore’s velocity. They were followed quickly by Embrace, a new band from Ian MacKaye, the singer of Minor Threat and co-owner of Dischord Records. MacKaye was a hardcore figurehead, so it was significant when he moved away from it towards emo. Embrace had lyrical themes similar to Rites of Spring but diverged even further from hardcore orthodoxy, utilizing stark bass lines and textured guitar playing derived from British post punk. Other bands like Dag Nasty and Gray Matter joined in and the moment it coalesced into an identifiable sound in 1985 was subsequently referred to as Revolution Summer in DC. Most of these groups lasted for less than a year, but that first wave cast a long shadow over the future of punk and hardcore. Later, in his emo history Nothing Feels Good, writer Andy Greenwald would describe these developments as a shift “from an individualised mass to a mass of individuals.” Communal confrontation had given way to individualist expression, and that would play out first as a relaxation of creative restrictions, and later as the careerist, self-centered, personal brand-focused tendencies emo would start to display in the 2000s. But the movement itself appeared to be over by the late-’80s, around when Fugazi (the new band from MacKaye and Rites of Spring’s Guy Picciotto) began to expand upon the ideas that had been percolating around DC hardcore for a decade.

Fugazi essentially began as an equal combination of Rites of Spring and Embrace. Throughout the ‘90s they would add elements of reggae, dub, noise, funk and even jazz into their songs. The second wave of emo concurrently worked out the possibilities of those threads —there were indie labels that tirelessly documented their region, like Jade Tree on the east coast, and regional scenes with signature sounds, like the New Jersey melodic punk and hardcore songs of Lifetime and Saves the Day. Mike Kinsella from Illinois took up Fugazi-like experimentation with the expansive math-rock he pioneered in the definitive Cap’n Jazz, Joan of Arc and American Football. Sunny Day Real Estate and Modest Mouse turned anguish into massive storms of guitar that mirrored the landscape of their native Pacific Northwest. Jawbreaker and The Promise Ring used a type of Smiths-influenced pop-punk to deconstruct how relationships were portrayed in pop music.

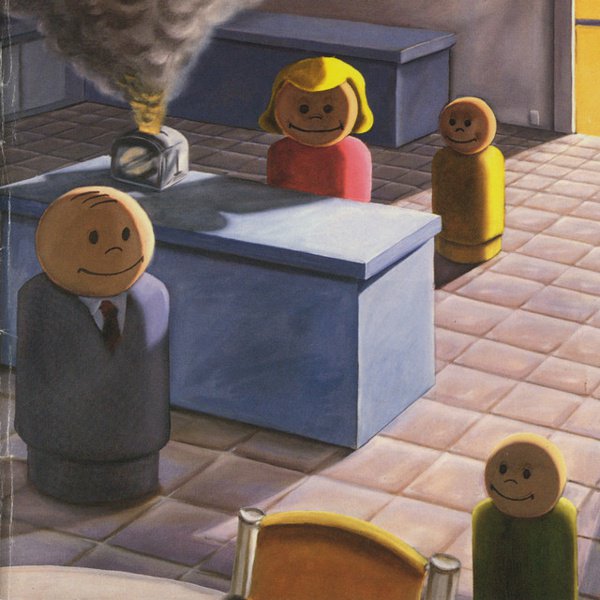

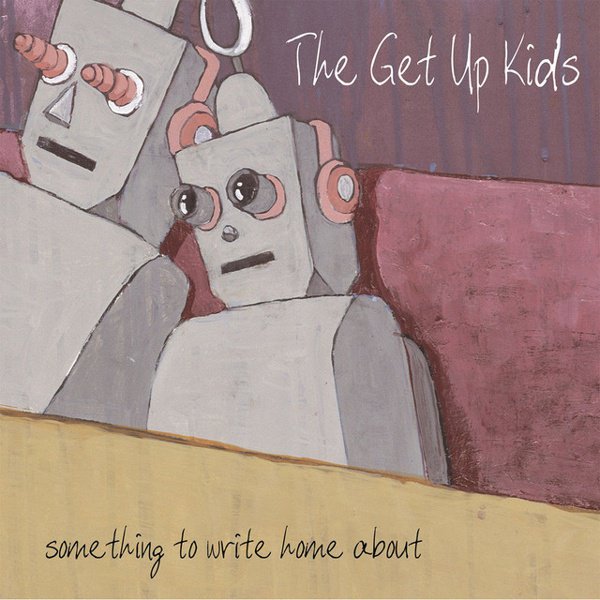

The boundaries between ‘90s emo and indie rock or hardcore or pop-punk were vague and porous. What was the real difference between indie rock torch bearers Sebadoh and The Promise Ring? Both were defined by angsty homespun relationship dramas and bitterly jaded guitar rock. The singing on Sebadoh records, though, was typically deliberate and controlled in comparison to the unrestrained sob that permeated most emo songs. The romantic interactions obsessively exhumed in emo songs generally had a teenage perspective, with hard lines between who had done wrong and who had been wronged. When emo bands would try to branch out into more adult topics and perspectives, like The Get Up Kids after their late-’90s breakthrough, they would lose much of their original audience. Without that romanticized purity and idealization of youth, it isn’t emo. That two of the most important emo records of the decade were not made by emo bands only added to the ambiguity. Weezer’s excruciatingly confessional Pinkerton and Blink-182’s Enema of the State (the lead single’s original title was “Peter Pan Complex”) could also be considered alt-rock/indie and pop-punk respectively, but their vast influence on almost everything that came after cements their emo status. As early as 1999, The Get Up Kids combined both strands into the archetypal Something to Write Home About and set the tone for the next decades of the genre.

The third wave, starting at the turn of the century, ended up erasing some of the most attractive aspects of emo – musical idiosyncrasy, genuine self-reflection, sincere attempts to bypass the mainstream music industry – in favor of a more musically diverse version of pop-punk. It was to be the last form of rock music to be a commercially dominant force, and regular appearance in the upper reaches of the Billboard charts by the era’s top acts would have been unthinkable just a few years prior. Bands like My Chemical Romance, Fall Out Boy, and Taking Back Sunday used the infrastructure of ‘90s mainstream punk like the Warped Tour, Fuse and the labyrinthine network of independent record labels to launch platinum-selling careers and arena tours. At its best, 2000s emo paralleled the 1960s garage bands and could be thrilling, trashy fun and occasionally moving. An unending stream of new bands meant plenty of excellent singles, a few great albums and lots of regional styles. “Helena” by My Chemical Romance and “Misery Business” by Paramore are classics of the form. The defining look of the time – swept asymmetrical haircuts, eyeliner overdoses and ostentatiously tight outfits got progressively more cartoonish, but they tapped into the eternal rock and roll impulse to freak out anyone older than 20. The previous eras of emo musicians shunned the spotlight but rock stardom was a primary goal of many of these new bands, and with the pioneering use of brand partnerships and exploitation of early social media platform MySpace, emo was a huge subculture with an enormous teen fanbase. Panic at the Disco and especially Paramore had some fine moments, but they had little in common with their progenitors’ punk and hardcore roots. By the end of the decade, the music industry was in shambles from the rise of the MP3, emo was creatively bankrupt, and the bottom fell out commercially.

The increased visibility of emo in the 2000s highlighted many of its inherent problems. Misogyny was a big one. By that point, one of the only major emo acts in almost three decades to even have a female singer was Paramore. Some of the lyrics that the boys in the bands wrote were stalker-like violent revenge fantasies. The insular nature of the genre led to emo bands whose only influences were other emo bands. It was everything its 90s iteration seemed to be rebelling against – chauvinistic, heteronormative, musically conservative, nakedly careerist. It had become formulaic, vapid, cliche; the equivalent of late-80s hair metal. Something had to give. Some of the more metal-tinged bands, like A Day to Remember, were absorbed into commercial metal and hard rock circles, while Fall Out Boy and Paramore were enormously successful while veering far away from the sound that had made them famous. Young bands began to shed the genre’s excesses, and went back to basics, having more in common with the second wave – bands like Into It. Over It and Joyce Manor were scaled down and shared the urgency of the best ‘90s groups. But there was a sense in the fourth wave that little ground was being broken.

By the mid-10s, underground rappers known for releasing music on Soundcloud began to absorb the emo sound and style into their music. It was a remarkably seamless integration, an obvious move in retrospect. Young hip-hop musicians Lil Peep, Juice WRLD and XXXTentacion found huge streaming and pop success by basically becoming emo singers. By the end of the decade, emo-themed nights at clubs around the US were massively popular, and the reunion tours of My Chemical Romance and others began. Robert Pattinson’s depiction of Batman was described by more than a few critics as having an emo aesthetic. Rapper Machine Gun Kelly scored a pair of chart-topping albums with his pivot to pop-punk and emo. For better and for worse, emo was culturally entrenched, and the desire to scream away the pain of your first heartbreak has proved to be an evergreen staple of the pop charts.