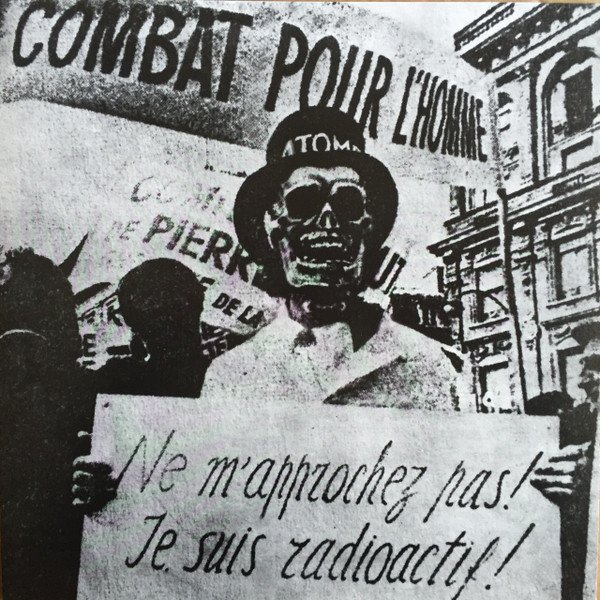

It’s not too hard to understand why Italian underground music was so creative, so profligate, so urgent across the seventies, at least if you believe that disrupted societies intensify creative impulses. That decade came to be known in Italy as the Anni di piombo – the Years of Lead – an extended period of political and social upheaval, in fact, that starts in the late sixties, roughly in line with student and worker uprisings across Europe and extends through to the late eighties.

This period in Italian history is marked by terrorism from both far-right and far-left organisations. The far-right targeted and bombed social infrastructure – railway stations, piazzas – while the far-left organisations, such as the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse), were responsible for kidnapping and assassinating former prime minister Aldo Moro. During the seventies, there was also increased social unrest; collaboration between labour movements and student activism; the development and sustenance of militant movements like Lotta Continua and Potere Operaio; the free radio broadcaster Radio Alice; powerful developments for the Italian LGBTQ+ movement; the radicalised Movimento del ’77; the severing of connections between the Italian Communist Party and the Autonomia Operaia…

In short, it was an incredibly turbulent time. Across the same decade, and no doubt both in the shadow of, and in at least ideological allegiance with, some of the progressive movements and developing conversations of the time, Italian popular music seemed to open to multifarious influences. Italy seemed particularly seduced by progressive rock, and their contribution to the genre’s development is both profound and lasting, both through the more over-the-top ‘symphonic’ prog groups and a more experimental, avant-garde side to prog.

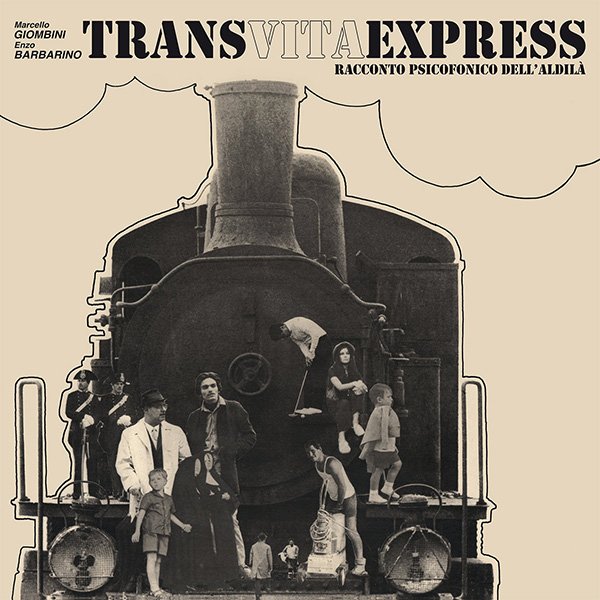

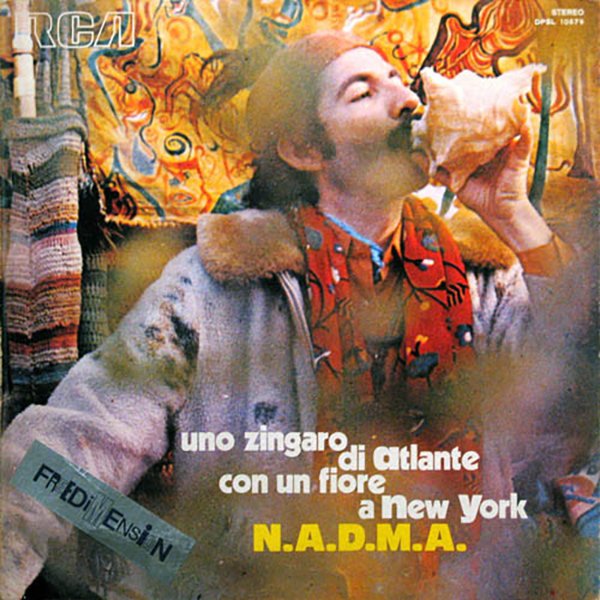

Similarly, developments in modern classical and the avant-garde were communicating across the seas and the continent, and a radical underground was quietly fomenting in Italy, across various cities and through various cells of creative engagement. Coupled with an industry of soundtrack music that was pretty much peerless – headed up by legendary figures like Ennio Morricone and Piero Piccioni – a contemporaneous explosion in creative and experimental film and horror and giallo, and the ongoing development of Italian library music (recorded often as background for television broadcast and film)…

Well, there was plenty going down in Italy. That this is but a provisional and far from all-encompassing snapshot of everything that was happening tells us that Italy was working at a particularly fierce creative clip through the seventies. Their underground seemed in productive allegiance, at times, with the mainstream, and if there’s a key figure to this guide of significant and sometimes underheralded albums, it’s prog-turned-avant-turned-pop-star Franco Battiato, whose run of eight albums across the decade is a near-peerless narrative of progressive rock turning into hardline classical minimalism. He brought his friends along for the ride, too – albums from Giusto Pio, Juri Camisasca and others probably wouldn’t exist without Battiato’s spirit and generosity,

Battiato’s turn to mainstream pop in the early eighties didn’t necessarily signal the end of an era – after all, Roberto Cacciapaglia, another key figure in the Italian underground, did much the same with the bizarre and wonderful Ann Steele Album. The lines between under- and overground seemed quite fluid, at the time, in Italy, at least looking from the outside in. And yet there did seem to be a turn from the tougher edges and more radical edits of albums by the likes of Pierrot Lunaire (Gudrun) and Nascita della Sfera (Per Una Scultura Di Ceschia) to music that was more ambient, ‘fourth-world’, exoticised: the minimalism got gentler, less rigorous.

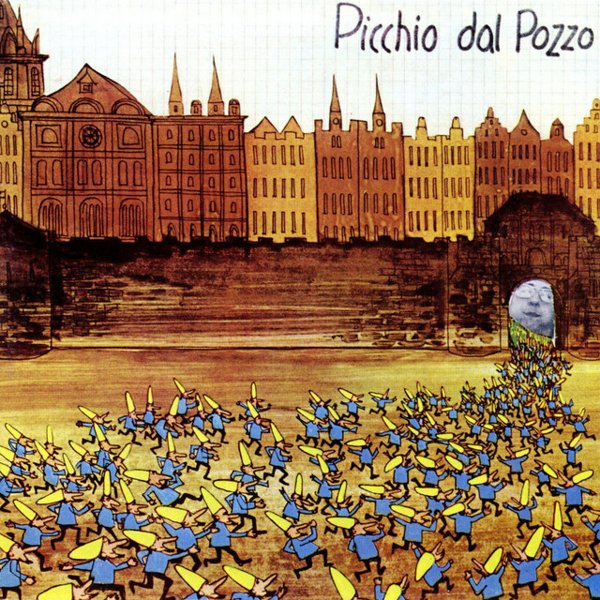

To be fair, that narrative was played out across the globe in various ways. But this guide was intended to celebrate the breadth, the depth, the wildness, the ideological and aesthetic rigour of Italian underground music of the seventies. With logic sometimes found wanting, I recognise there are names missing – Area / Demetrio Stratos, Claudio Rocchi, Il Balletto Di Bronzo… But the list here takes in plenty – Battiatio and his collaborators; the prog-folk of Saint Just and Lucio Battisti; minimalist composition, mangled tape edits, and yet more.

Some of this material has been reissued by labels, many from Italy, and I’d fully recommend checking out the catalogues of current imprints such as Die Schachtel, Black Sweat, and Soave, not just for their excellent archival work, but also for the way they often interface the old with the new, in a tacit recognition that the avant-garde and underground in Italy is every bit as vibrant now as it was fifty years ago. But we are in different times. And each of the albums in this guide is both eternally resonant, and a snapshot of just how strong the creativity coursed through the veins of the Italian counterculture across ten long years.